This is the place. At night you can almost see it… At night, you can almost imagine… You shouldn’t have come here.

Welcome back. As explained recently, I’ve been on a short hiatus from my reading of the Marvel Universe. Still not quite ready to return to it.

However, I find myself with a bit of time thanks to having contracted a bug that’s going around, and thought I could return to my series on reading great comics. I call it a series, though this is only the third entry. But hopefully we’ll be getting more.

The format is similar to my posts about the Marvel Universe, where I pick up a single comic and read it and write down my thoughts as I do. Except where my Marvel reading is guided by the internal chronology of those stories, I will here be picking up my very favorite comics, specifically those not focused on the early Marvel Universe. We’ve talked about a favorite issue of Sandman and Astro City… it’s time for Swamp Thing.

Reflections on how I came to this story

Before we dive into the issue, I’d like to reflect on my personal background, where I was in my comics reading and what I knew about Swamp Thing prior to picking up this comic.

For the first several years of my comics reading, I read exclusively superhero comics, and mostly Marvel superhero comics. By the age of 16 or so, I was ready to start branching out, but slowly. My next step would be superhero comics that didn’t quite fit the usual mold, starting with Inhumans by Paul Jenkins and Jae Lee.

By 17, I was working in a comic store in exchange for comics, and could thus afford to experiment more with my reading, and sought out the famous and supposedly great comics of yesteryear in their collected form. I hit quickly on the works of Alan Moore, and picked up three of his kind-of-superhero-kind-of-not masterpieces in a short amount of time aged 17-18: Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and Swamp Thing. I couldn’t tell you today which I read first, but I loved them all, and Moore quickly became and remained my favorite comic writer.

As to the character of Swamp Thing, I’d encountered him at least twice before. In my youth, I’d seen the first Wes Craven Swamp Thing film, probably at too young an age for my mother’s taste. It hadn’t made an impression, and I recalled little about it by the time I got to these comics. I only rewatched it for the first time in decades just the other day, as part of my diligence for preparing this post. I also watched its sequel for the first time. Neither are particularly good films. The sequel is better.

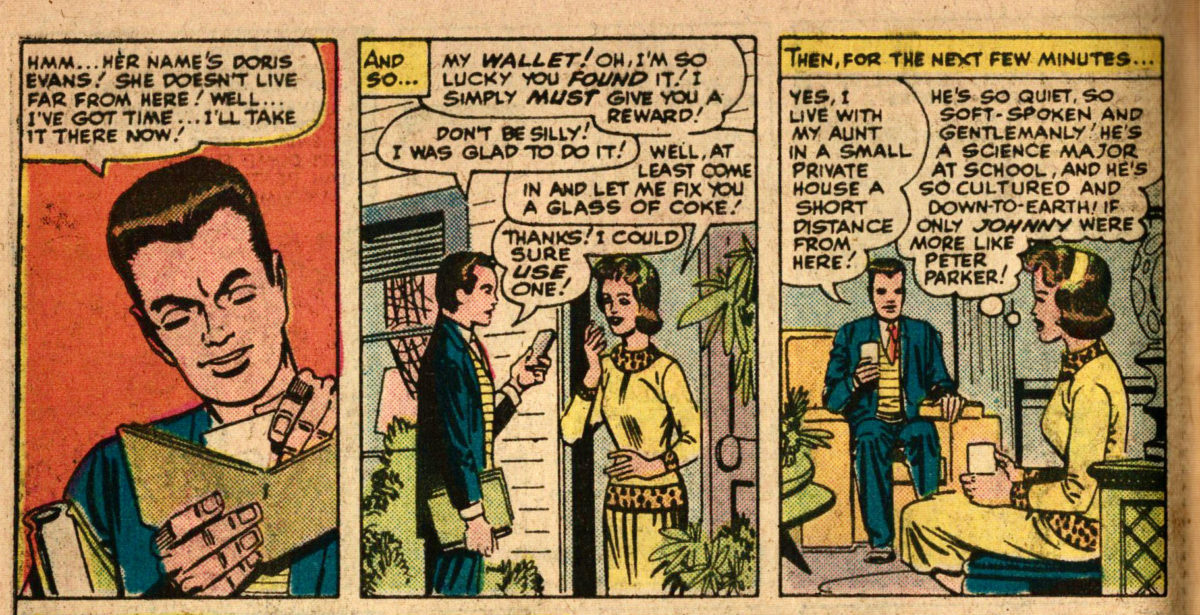

I’d also read the introduction of Swamp Thing from House of Secrets #92 at some point in my youth as part of a boxed set of introductions of famous DC heroes called Silver Age Classics.

This story I did recall, though that recollection confused rather than aided my attempts to understand Moore’s book.

We’ll recap it that you may share in my confusion.

The opening page features the biblical Cain and Abel hunting for snipes.

We then cut to the story of Swamp Thing. It takes place around 1900; we begin with the internal monologue of a swamp monster approaching an estate.

We look inside to meet Linda Olsen Ridge, wife of Damian Ridge, and widow of Alex Olsen, Damian’s lab partner who had died in a freak accident.

We then see Damian’s point of view, and learn Alex’s death had not been an accident. Damian had murdered him out of jealousy over Linda, and was now planning to murder Linda before she figured out the truth.

We then see the point of view of the swamp monster again, who breaks in to rescue Linda. He stops Damian, but Linda is horrified of him. Because he is mute and monstrous, he cannot explain that he was once Alex Olsen. So he walks sadly into the night.

The tale was by Len Wein and Berni Wrightson.

It is in no way clear how we get from that, my first Swamp Thing story, to this, my second. Somewhere in between, Swamp Thing went from being a mute creature named Alex Olsen from a century ago to a talkative creature named Alec Holland in the present. And somehow, he ended up dead on an autopsy table.

I had one more hint, though. The collection I purchased comes with an introduction from Alan Moore, one of the best introductions to a comic I have ever read. While much of it is specific to Swamp Thing or to DC horror books, lots of it could help a new reader acclimate to Marvel or DC superhero books.

For example, Moore talks about the concept of a shared universe with a mix of cynicism and enthusiasm. What it means to write a horror comic that takes place in the same world as Superman comics. Why that’s a bad idea, and why it’s maybe not such a bad idea. I’m already starting to butcher his words in my summary, so let me quote an excerpt from the introduction.

The very first thing that anyone reading a modern horror comic should understand is that there are great economic advantages in being able to prop up an ailing, poor-selling comic book with an appearance by a successful guest star. Consequently, all the comic book stories produced by any given publisher are likely to take place in the same imaginary universe. This includes the brightly colored costumed adventurers populating their super-hero titles, the shambling monstrosities that dominate their horror titles, and the odd grizzled cowpoke who’s wandered in from a western title through a convenient time warp. For those familiar with conventional literature, try to imagine Dr. Frankenstein kidnapping one of the protagonists of Little Women for his medical experiments, only to find himself subject to the scrutiny of a team-up between Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot. I’m sure that both the charms and the overwhelming absurdities of this approach will become immediately apparent, and so it is in comic books: Swamp Thing exists in the same universe same universe as Superman, the same world as Batman and Wonder Woman and all the other denizens of the cosmos delineated within the pages of DC Comics’ various publications.

As I said above, this approach has both its charms and absurdities. The absurdities are obvious: to work properly, horror needs a delicate and carefully sustained atmosphere–one capable of being utterly ruined by the sudden entrance of a man in green tights and an orange cloak, especially if as a character, he’s fond of puns. The charms are much harder to find, but once revealed, can actually be rewarding. The continuity expert’s nightmare of a thousand different super-powered characters coexisting in the same continuum can, with the application of a sensitive and sympathetic eye, become a rich and fertile mythic background with fascinating archetypal characters hanging around, waiting to be picked like grapes on the vine. Yes, of course, the whole idea is utterly inane, but to let its predictable inanities blind you to its truly fabulous and breathtaking aspects is to do both oneself and the genre a disservice.

Imagine for a moment a universe jeweled with alien races ranging from the transcendentally divine to the loathsomely Lovecraftian. Imagine a cosmos where the ancient gods still exist somewhere and where whole dimensions are populated by anthropomorphic funny animals. Where Heaven and Hell are demonstrably real and even accessible, and where angels and demons alike seem to walk the earth with impunity. Imagine a planet where exposure to dangerous radiation granted the gift of super-speed rather than bone cancer, and where the skies were thus filled by flying men and women threatening to blot out the sun. Imagine a place where people were terribly good or terribly bad, with little room for mediocre in between. No, it certainly wouldn’t look very much like the world we live in, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t be every bit as glorious, touching, sad or scary. With this kind of perspective, the appearance in these pages of the Justice League of America or vintage DC super-villain Jason Woodrue should be less unnerving than it might otherwise have been to the uninitiated.

Alan Moore

The other thing he warns of is that the story of Swamp Thing neither begins nor ends. I, like many, would begin reading Swamp Thing here, but this was issue 21. And not even issue 21 of the first Swamp Thing series. Alan Moore’s final issue was 64; not the final issue of Swamp Thing.

Issues 21-64 make a good read, a satisfying read. But not one without loose ends before and after. Issue 21 is a good beginning, but not the beginning. The beginning was the tale related above. And 64 is a good ending, but not the ending. That hasn’t come yet, 40 years later.

Issue 21 isn’t even Alan Moore’s first issue. He came on with issue 20, but the collection neglects to include that. Issue 20 is called “Loose Ends”, in which Alan Moore attempts to resolve the dangling plot threads of outgoing writer Martin Pasko, to get a clean start for the character.

I like how he described the working arrangement in regards to his run on Marvel’s Captain Britain, that he had to continue a story he’d “neither inaugurated nor completely understood.”

He cleans up those loose ends in the most efficient way he can, by having Swamp Thing’s enemies shoot him in the head and kill him.

The Anatomy Lesson

And so we begin a new era of Swamp Thing. With Swamp Thing dead and undergoing autopsy.

Let’s dive in.

Saga of the Swamp Thing #21. Colors by Tatjana Wood. Letters by John Costanza. Edited by Len Wein.

The first thing to discuss is the perspective from which this story is told, as there are a few different perspectives at play, and the comics medium is well-positioned to make unique use of them.

One person, Jason Woodrue, will narrate the story from a first person point of view. What’s interesting is the three different perspectives he has. Much of the story is told in past tense, as our narrator fills us in on recent events. However, the story opens in the present tense. “It is raining in Washington tonight.”

The first page has two different perspectives on the present. For parts of it, Woodrue is narrating what is happening right now, as he sits in his penthouse having a drink. For parts of it, he is narrating in a hypothetical tense, as he guesses what is happening right now, describing events he is not privy to, but can make an educated guess about, but uncertain if he’s describing events of the recent past or near future.

“He’ll be pounding on the glass right about now… or maybe not now. Maybe in a while.”

“Yes, I rather think there will be blood.”

We’ll see later in the issue the unique strength of the comic medium for stories told from this hypothetical point of view.

I love the first page. From the words to the images, it’s evocative. The mood is set. This is a horror story.

Woodrue’s window is slatted into a grid. To the point where looking at him through the window is just like looking at comic panels, and the artists play with this effect.

The logo is placed over the silhouette of a corpse, reminiscent of Otto Preminger’s film, Anatomy of a Murder. (Also rewatched the film to prepare for this post. Probably not strictly necessary, but a good movie.)

We then transition to the past tense that will dominate the story, when Woodrue first met the person he calls the Old Man. The person he now imagines to be in trouble.

We get a minor detail which may be important. There’s no human security. It’s all electronic, and controlled from a single console.

They open a freezer to look upon a corpse, who was shot and killed about two weeks ago by the Old Man’s people.

Finally, on page 3, we meet the Swamp Thing. At least, we meet his corpse. “…gray, brittle, tattooed by frost, quite dead…” A wild way to begin Alan Moore’s epic run of 44 issues.

The Old Man then gives a brief summary of the origin of Swamp Thing. Dr. Alec Holland had been working on a bio-restorative formula to promote crop growth. His lab was sabotaged and an explosion seemingly killed Holland, but instead transformed him into the Swamp Thing.

The story now takes a science fiction turn, which is likely why we’re discussing it today. Science fiction is my favorite genre; horror is not. But as horror stories go, this one’s good.

The strength of this Swamp Thing era will be its ability to blend horror and science fiction with romance and superhero tales.

The mystery at the heart of this issue is how the formula designed to make crops grow turned a man into a swamp monster. In general, that’s the type of question one is supposed to shrug off, to instead just enjoy a monster story. But this comic doesn’t want to back off it at all. Holland had worked with his wife. She had also been exposed to the same formula and also killed. Why was she unaffected?

The formula was not designed to affect human tissue and an analysis of the formula in her corpse showed it had not affected her tissue. Dr. Woodrue is tasked with solving the riddle of the Swamp Thing.

We then see that Dr. Woodrue’s skin is just make-up. His true form is not unlike that of the Swamp Thing. He is the Floronic Man.

Then begins the autopsy at the heart of the book. The art takes us first back to the present to see Woodrue sipping his drink as the narration takes us into the hypothetical present before both return to the past.

As he examines Swamp Thing’s body, he finds organ-like substances made out of vegetable. Yet no vegetable material can replicate the functions of our organs. What Woodrue finds is objects in the form of lungs, a heart, and a brain… but which do not function, and never did or could. The mystery deepens.

The experiments continue, and tensions between Woodrue and his employer grow. At their heart are common conflicts between the researcher and the businessman.

We then see the Floronic man in all his, err, glory, showering off his fake skin in the present, as he continues to narrate in a mix events of the past, present, and possible present. The recounting of the past has caught up to just hours ago.

“I am thinking about the old man, there in his office when I went to tell him of my discovery, late this afternoon. I am thinking about melting frost, and trickling water… and something strong and soft and green thrusting through the dead and petrified grayness.”

On the first page, as Woodrue described the old man possibly pounding on glass, the art showed a hint of that. Was the art showing us events transpiring elsewhere or simply Woodrue’s imagination? I imagined the latter.

But now something has shifted. Woodrue expects that something is emerging from the corpse of the Swamp Thing. He is an expert and has good reason to guess this. The art could be depicting what Woodrue is imagining, but that’s not how I interpret it. I think the art is showing us what is actually happening.

The words are Woodrue’s, narrating from an uncertain third person viewpoint; but the art can give us its own viewpoint, an omniscient third person able to move its camera into the room and show us events as they transpire. And then the comic can juxtapose these viewpoints. The text which guesses at events, and the art which shows us that those guesses are spot on.

And now we are back to hours earlier, as Woodrue lays out the answer to the mystery, like a classic detective explaining a murder plot. He begins with explaining an experiment on planarian worms, in which worms were trained to run a maze, and then cut to pieces and fed to other worms… who could then run the maze as though they’d been trained. The conclusion is that consciousness and memory can be passed on as food.

I read up on the classic experiment by Thompson and McConnel from 1955. Woodrue’s description isn’t far off. The experiment was about avoiding particular light sources and the conclusion was about memory, but it’s close. The results of the experiment were never reproduced and its conclusions generally rejected. But we’ll allow it.

The old man grows impatient. He’s a bottom line type of guy with no ability to abstract, whereas the academic is inclined to explain things carefully and thoroughly. I sympathize with the academic.

We then see more detail on Swamp Thing’s origin. The dynamite, the explosion. However, we now get it with a twist. Woodrue’s interpretation is that the explosion killed Holland and his corpse was sent into the swamp, and the formula with it. The formula did not affect Holland, but it affected the plants in the swamp. As Holland decomposed, his body was ingested by the plants. And, like the worms, his consciousness was ingested.

“We thought that the Swamp Thing was Alec Holland, somehow transformed into a plant. It wasn’t. It was a plant that thought it was Alec Holland.”

And so it reshaped itself into a form as close to Holland as it could muster, and walked the world thinking itself Alec Holland. But Alec Holland is long dead.

Having received the key insight, the businessman has no more use for Woodrue, and fires him immediately.

The old man goes on an anti-intellectual screed about his superiority as a man of business. “I am not, in your terms, an intelligent man. I am merely shrewd… I do not need to know how this computer works to know that if I push this little button, all the sprinklers start up or the doors open and close.”

The next page is beautiful. Both men believed they had the power. But Woodrue knew exactly how the computer worked… the thermostats, the door locks.

That’s how he knows what’s happening now.

“You can’t kill a vegetable by shooting it through the head.”

Swamp Thing wasn’t killed by the bullet, merely shocked, and then frozen. Once thawed, he will awaken. Woodrue imagines the Swamp Thing will find his file, and the art suggests he is right.

Swamp Thing has so far in his history acted like a superhero, not a killer. But Woodrue realizes the truth he’s just discovered may have changed him. That’s why he suspects the old man is in trouble. That’s why he suspects there will be blood.

“He never was Alec Holland. He’s just a ghost. A ghost dressed in weeds.”

End Notes

While this issue is a satisfying tale in and of itself, it leads into a conflict between Swamp Thing and Floronic Man, a conflict the Justice League will take part in. Then we get a horror story involving a monkey demon and another classic DC character, Jason Blood. From there, the horror gets starker, to the point where the Comics Code seal is removed for the rest of the series.

The core of the book will become about Swamp Thing’s relationship with the woman, Abby. When she is killed, he’ll go on a Dantean quest to rescue her, finding Heaven and Hell populated with classic DC characters. Soon, they’ll confess their feelings for each other and consummate their strange relationship.

The series will introduce a man named John Constantine, who leads Swamp Thing on a global quest to avert horrors and stop an ancient evil that is rising.

While away, conservative authorities will arrest Abby for her unnatural relationship, and Swamp Thing’s war to free her will bring him into conflict with Batman, which will end with Swamp Thing being killed. Again.

Of course, he is not really dead this time either, but trapped in deep space on an epic science fiction quest to find his way home to the woman he loves.

All he wants, all he ever wanted, is to live at peace in his bayou with Abby.

“Good God is in his Heaven. Good gumbo’s in the pot.”

It’s one of the best comic sagas I have ever read, and I think of it as a turning point for American mainstream comics. Any superhero comics older than Swamp Thing feels like an old comic to me. And anything newer feels modern, but also like an attempt to tell a story like Moore told this one.

The Creators

As I’ve said, I think Alan Moore is the best writer in comics. He no longer writes for comics, having been badly mistreated by basically the entire industry. In fact, you can see in this comic an almost prophetic take on his career. He is the creative genius, an artist where Woodrue is a scientist. And he would deal with many publishers and businessmen just like the old man Sunderland. People who did not appreciate him and who took advantage of his genius, then threw him away.

But before finally walking away, he worked with some of the medium’s best artists to give us its best stories. I already mentioned Watchmen and V for Vendetta. Other masterpieces include From Hell, Promethea, and Lost Girls.

But his list of great works is endless: The Ballad of Halo Jones, Top Ten, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, Batman: The Killing Joke… the list goes on.

No writer in comics has a resume like that.

Bissette is best known as a horror artist, with this his most famous work. Totleben was a frequent artistic collaborator. They co-published their own horror anthology, Taboo, which is where Moore debuted From Hell and Lost Girls. Both would collaborate again with Moore on the superhero throwback series, 1963. Totleben worked with Alan Moore again on his superhero series Miracleman, a legally required rebranding of Marvelman.

I’ll note that in preparing this post, I decided I wanted to read the original comic. I’d purchased the story in collected form over 20 years ago. That copy is well-read but still with me. I wanted to see what the original looked like. The best price I could find was $50. Prior to that, I’d never spent more than $30 on a comic. And only in the last few years did I decide $30 was an acceptable price for the occasional comic. I held to a strict $20 limit for many years and acquired many tens of thousands of comics I wanted to read within those bounds.

For this comic, I made my first exception. I hope to not make too many others.

Reading Great Comics

This is the third entry in our “reading great comics” series.

very clear and good article easy to understand. Thank you